Cultural Heritage

Architecture and art in Roncesvalles

Its combination of history and geography have endowed Orreaga- Roncesvalles with a significant artistic foundation.

Its architecture, whose original function was to shelter walkers and pilgrims, coalesced in buildings of great quality,

especially the Collegiate church from the 13th century

- Church of Santa María

- San Agustín Chapel

- Claustro

- Chapel of the Espíritu Santo

- Church of Santiago

- Itzandegia

- Museum

- The Priory House

- Bell tower

- The houses of the Beneficiados

- Pilgrims hostel

- Mill

- Inn

- Chapel of San Salvador

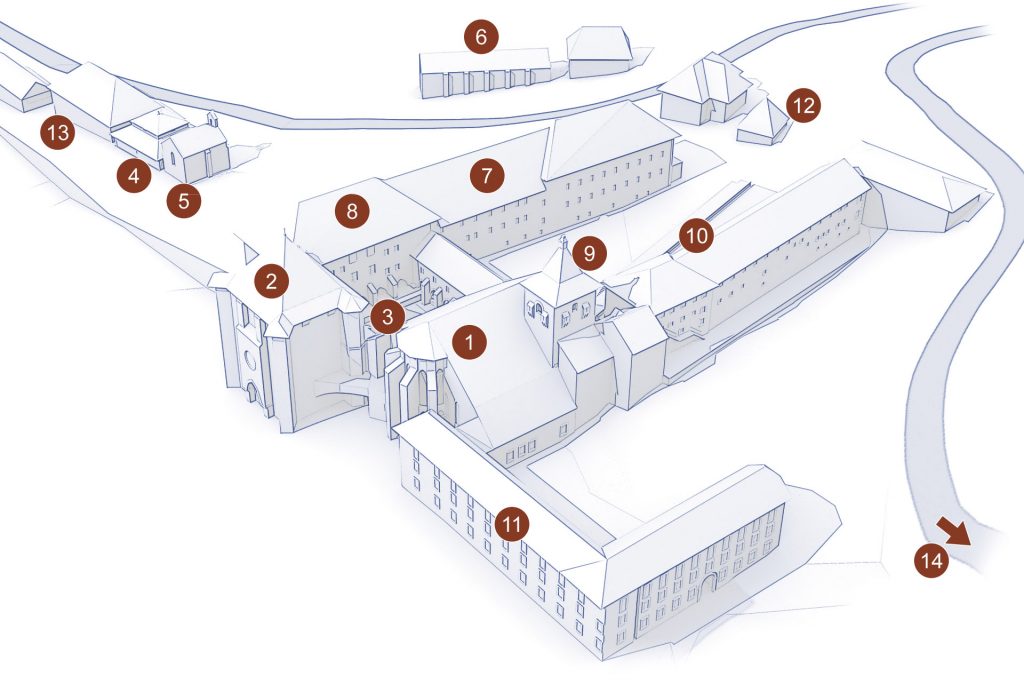

The urban centre

As an urban development, Roncesvalles has three focal points that constitute the centre of a continuous space. The first is the access esplanade which has the Priory House and Museum-Library as a backdrop. The second nucleus of the collegiate complex is hidden by this first line of buildings. It is an almost enclosed space which forms a large rectangular square accessed by a small tunnel with a depressed vault. Laid out over various levels, the upper part is occupied by the Houses of the Beneficiados. The third area is another rectangular patio enclosed by houses where the Hospital stands, which was built at the beginning of the 19th century and today functions as a youth hostel.

Other public buildings include the old mill, built at the end of the 18th century and totally renovated as a tourist information office, and the simple dwellings next to the Beneficiados.

Notable amongst the buildings of an eminently public nature is the hostelry or inn, which is the first building you come across on arriving from Burguete and which was built for this purpose in 1612.

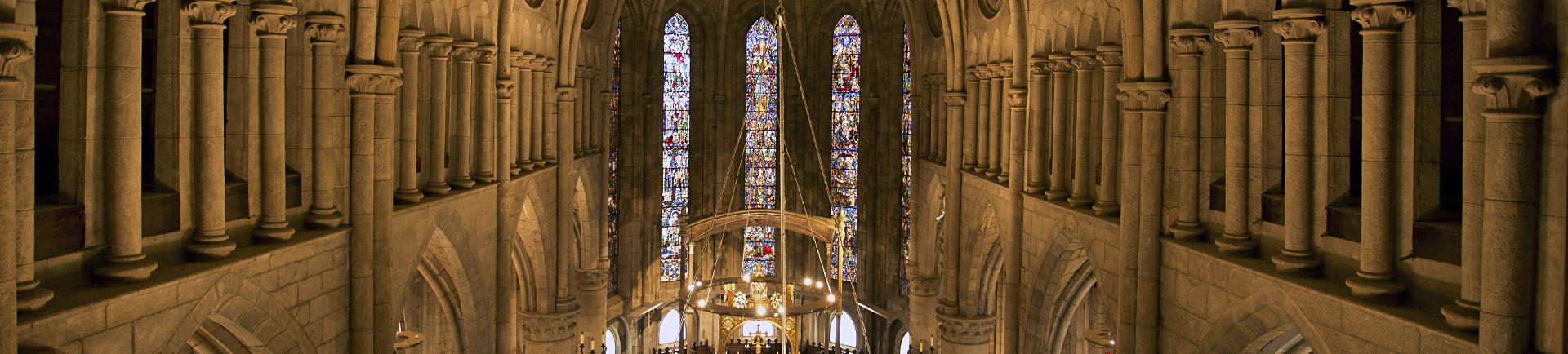

Collegiate church of Santa María

The Collegiate church of Santa María is the most emblematic building in Orreaga- Roncesvalles and the one that most clearly alludes to the powerful community of Augustine canons who lived there from its foundation. It is also the finest example in Navarre of not only French Gothic, but the very purest I’Lle de France style, and houses a beautiful image of the Virgin from the 14th century.

The hypothesis that there was a church in Orreaga- Roncesvalles before the existing 13th century one is accepted, although opinions differ as to whether this was located in the same place or in the location occupied by the chapel of Espíritu Santo.

The present church was built under the patronage of Sancho VII “The Strong” (1194-1234), who chose it as his burial site. Researchers give different opinions on the exact date of construction, but it is known that it was at the beginning of the 13th century, sometime between 1215 and 1221.

The Collegiate subsequently suffered serious damage, mainly caused by fires in 1445, 1468 and 1626. At the beginning of the 17th century its state of deterioration and virtual abandonment prompted its reconstruction. The building initiative involved the entire Collegial site, particularly the church and cloister.

Work entailed covering over the Gothic interior and giving it a Baroque style, with the exception of the presbytery and the section of nave before it, where Gothic elements are still visible.

Layout of the Church

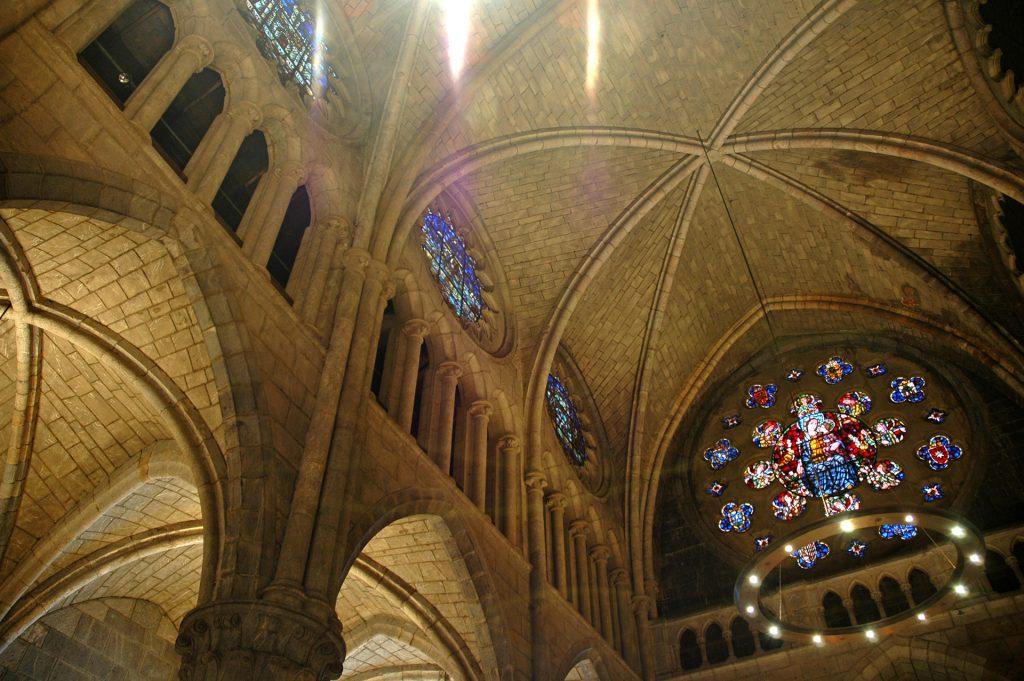

The church, as can be seen in the present day, has three naves, the central one being double the width of the side naves which are divided into five sections, in addition to which the central nave has a pentagonal chevet; the side naves end in a straight line. The support system is provided by cylindrical pillars of alternating thickness which separate the naves, supported on a pedestal and topped by a capital decorated with a double girdle of “crochets” in a very simplified style. These pillars serve as a support for the pointed longitudinal arches and the small columns on which the roofing rests. The triforium runs over the longitudinal arches, formed on each section of the central nave by four small pointed arches over small columns with the same type of capital; a gallery free from partitions that leads to the “ox-eye” window and features a sequence of pointed arches as the sole decorative element. This characteristic Gothic feature translates into the chevet in the opening of large windows, decorated with modern stained glass.

The central nave is covered by two sections of sexpartite vault with beaded ribs, except at the crossover which is half-ribbed to thus join on to the roof of the apse whose radial ribs fan off the single decorative keystone. The ribs of the roof are supported by slender individual columns which reach to the floor of the apse and are supported by the cylindrical pillars in the nave. The lateral naves are covered by a simple groin vault set at a lower height than the central one. On the frontal wall of each of them are two pointed stained glass windows.

360º view of the interior of the church. Click and drag or move your phone to change the view.

Façade of the church

The only original element of the façade is the door aperture with its three archivolts. The façade was originally very simple and consisted of a pointed door flanked by rose windows and a pointed window some way above the door.

Presbytery. Virgin of Santa María de Roncesvalles

A magnificent sculpture of the Virgin of Roncesvalles presides over the church. This wooden Gothic figure plated in silver dates from the middle of the 14th century and was made in the French city of Toulouse. The sculpture perfectly transmits the Gothic spirit, in terms of intimacy, naturalism and familiarity.

The seat and cushion are also highly ornamental. The latter is decorated with a dense network of diamond shapes and the chair with a series of trilobe arches on the front.

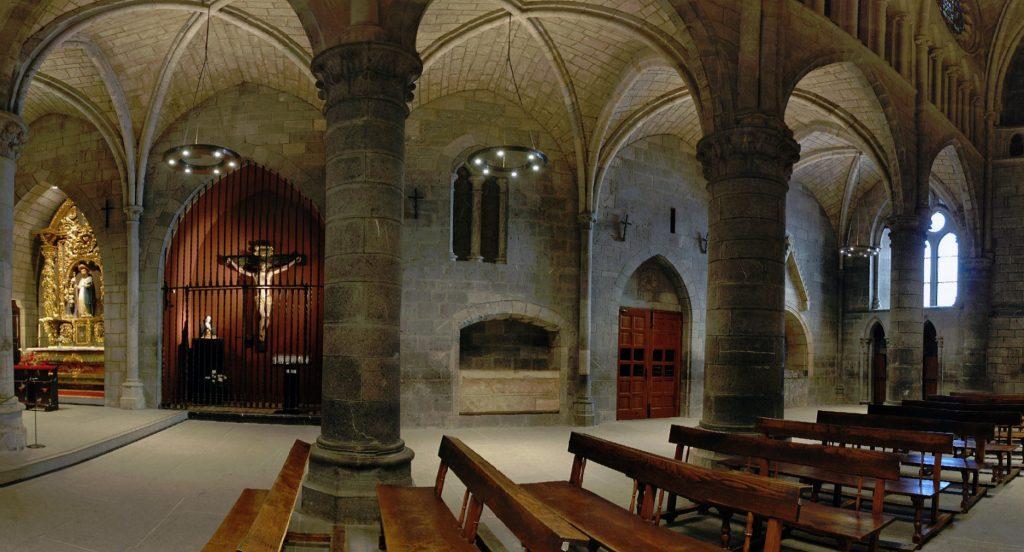

Chapel of Santo Cristo

This is a small chapel located off the right-hand lateral nave of the church. Closed by bars since the beginning of the 17th century, the chapel is presided over by a life-sized crucifixion from the 19th century. At his feet is a bust of the Dolorosa dating back to the 17th century.

In the same right-hand nave is an arcosolio-type sepulchre decorated with an inscribed cross inside a circle. In the next niche is the Egüés family sepulchre, framed by a pointed gabled arch.

Crypt

The church has a pentagonal crypt which includes the chevet and the transept, built to accommodate the steep slope of the land. The first section is covered by a half-barrel pointed vault and the chevet is covered by a handkerchief vault. Semicircular windows open up in the central expanse of the chevet. Although in a very deteriorated state, the pictorial decoration still survives, as does the Gothic configuration of ashlar stone. The church and the crypt are linked by a very steep staircase covered by a pointed barrel vault without transversal arches. Above this is the sacristy.

San Agustín Chapel

This chapel is also known as the Tower of San Agustín, the Royal Chapel and the Capitular Room. The eastern wing opens up into a triple arcade, a formula very similar to the Barbazana chapel in Pamplona Cathedral.

It has a square layout covered by a vault of intermediate ribs with much more styled rib couplings than those in the church, with decorated keystones. The vault is supported on four large semi-columns which give a rough representation of angels.

The chapel has a small open area in the eastern wall which acts as the chevet and is at a higher level. This area is rectangular in shape with a groin vault, the main keystone of which is decorated.

The exterior is made of cubic ashlar stone, giving it a certain fortress-like appearance, hence the reason that on occasion it was known as the Tower of San Agustín. Buttresses adjoining the corners and reaching up to the pyramidal roof reinforce the building which dates back to the 14th century.

In the centre of the chapel stands the sepulchre of Sancho VII “The Strong” which was installed in 1912, the date when the chapel was refurbished to commemorate the anniversary of the Battle of Navas de Tolosa. Of the original funereal tomb of the King, who died in Tudela in 1234, only the slab with the relief of the reclining monarch remains, surrounded by a delicate decorative frieze of vegetation which is dated at the 13th century, as it was at that time that Theobald I commissioned his uncle’s sepulchre. The rest of the sepulchral bed, with its trilobe arches, reflects the neo-Gothic fashion that reigned in 1912.

A small room in the western part of the chapel, a little higher up, with a groin vault and a keystone featuring Christ blessing, serves as the chevet of the chapel which, since at least the beginning of the 17th century, has been closed off by bars. At the beginning of the 20th century, chains and maces were hung up to commemorate the centenary of the Battle of Navas de Tolosa (1212), in which Sancho “The Strong” fought. The chapel was restored for this purpose in 1922, resulting in the majority of the modern features that are still in place today, including the stained glass windows.

On the floor, at the entrance to the little chapel, is the tombstone of the Prior Don García Juan de Viguria (1327 – 1346).

In the chapel of San Agustín it is also worth noting a series of sculptures associated with works in the cloister of Pamplona Cathedral. These are two capitals that represent Original Sin and the Expulsion from Paradise, and it is feasible that these formed part of the Gothic cloister. Also noteworthy are two praying statues of King Sancho VII and his wife, Lady Clemencia, positioned in one of the recesses of the tiny chapel.

Cloister

The cloister has a square layout and adjoins the church on the Epistle side. It replaced the previous cloister which collapsed under the weight of snow in 1600. The chronicles of Licenciado Huarte compare its exquisite decoration with the cloister of Pamplona Cathedral. This similarity would appear to be credible given the foundational relationship between the two churches.

Construction of the current cloister is widely documented as being 1606, the year in which the plans were commissioned, although work did not actually start until 1615 and went on until at least 1661.

The cloister is square yet irregular in shape, an irregularity which is replicated in the raised part, which is on a single level and features bays of different widths, buttresses of different numbers and sizes, and arches with different spans.

Three of the wings are covered by a flat roof with wooden beams and strong transversal pointed arches of rectangular section. Stylistically speaking, the arches make a reference to previous centuries although their solidity can be explained by the desire to achieve a structure that would withstand any eventuality. The Eastern bay, off which the chapel of San Agustín opens, is covered by a simple groin vault with semicircular transversal arches.

Several burial niches with pointed arches have been discovered embedded in the walls of the cloister, the remains of the original Gothic cloister.

Chapel of the Espíritu Santo

This chapel is also known as the “Silo of Charlemagne”, as according to tradition it is the burial site that the French monarch ordered to be built for Roland and the other knights who fell in the Battle of Roncesvalles.

Despite the fact that the chapel has undergone many transformations, it appears to be the oldest building still preserved in this area. It used to safeguard the stone that Roland split in two with his sword. Nonetheless, this association with the hero’s memory did not impede the chapel from carrying out its sacred functions.

It is believed to date from the 12th century and stands over a well which used to serve as an ossuary, with masonry walls and a half-barrelled vault in the same material. The chapel itself was built over the well, square in shape and with a simple groin vault. This part is at a higher level than the floor, and this is where at the beginning of the 17th century work began on a tiny cloister with a stone arcade on three of its four sides and a wall that served as a burial site for canons. The semicircular arches rest on square pillars with upper imposts.

Church of Santiago

This small Gothic chapel from the 13th century stands next to the “Silo of Charlemagne” and is a simple rectangular building with two sections which include an upright chevet and a simple groin vault. Simple cylindrical base columns serve as a support for the roof.

The exterior is also very simple, with walls of irregular ashlar stones, no buttresses, and a pointed arched doorway with a crismon (sacred monogram).

Used as a parish church up until the 18th century, this small chapel was left without worshippers for a long period of time until it was restored by Florencio Ansoleaga in the 20th century, opening up the small ox-eye above the door and adding the pilgrim’s bell.

Itzandegia

This early Gothic building (13th century) stands opposite the chapels of Santiago and Espíritu Santo.

Legend attributes it as the first sanctuary of the Virgin of Roncesvalles, or at least as the place where her image was kept following her apparition.

It has a rectangular nave in six sections whose roof is supported by transversal arches, and an exterior of irregular ashlar stones.

Its original function is unknown, as documentary evidence prior to the 16th century refers to it as a hayloft, a stables and a servant’s quarters.

These different functions explain the various modifications that have resulted in the total disfigurement of the structure and the building’s appearance.

Library and Museum

The Library and Museum of Roncesvalles occupy the building adjacent to the Priory House, forming a horizontal block. The building has three storeys and a small attic with an “ox-eye”. An arcade of fluted pilasters with eclectic motifs opens up in the second section of the building.

The Museum

The small museum on the ground floor of the Library building houses a large number of objets d’art that are representative of the Collegiate, including sculptures, painting and silverwork, as well as furniture, tapestries, coins and books of considerable bibliographic interest.

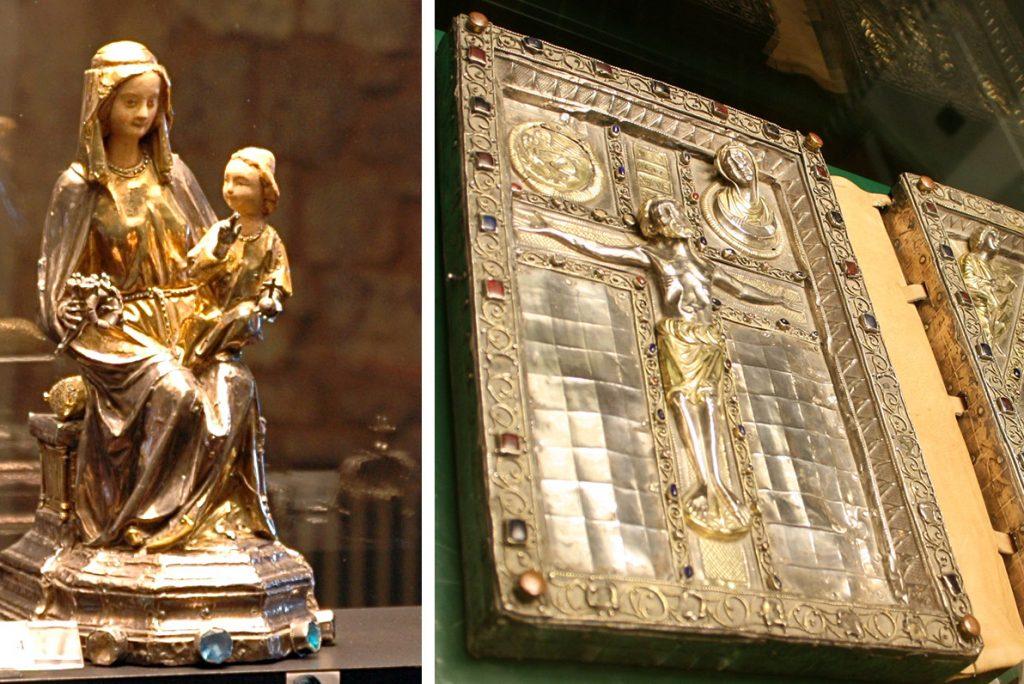

Sculpture

Notable amongst the sculptures are a Gothic statue of a seated female figure from the 14th century and a sculpture of St. Michael dating back to the second third of the 16th century.

The Museum also preserves some reliefs and statues that formed part of the High Altar of the Collegiate, made between 1618 and 1624, which were dismantled when the church was restored and partially redistributed in the parish of Yesa.

The sculpture collection is rounded of by an ivory Baroque Crucifix from the 18th century.

Painting

There is an impressive triptych of the Crucifixion, stylistically ascribed to the North European school of the 16th century, which was ceded to the Collegiate in 1720 by Jerónima Jiménez de Esparza. Its origin would appear to be Flemish.

Another noteworthy piece is the depiction of the Holy Family, created by Luis de Morales, which in appearance is similar to the one in the New Cathedral of Salamanca, especially in the central grouping.

Representative of the 17th century are a magnificent canvas of the martyrdom of San Lorenzo, a Baroque piece from the first half of the 17th century, and an interesting canvas of Judith bringing the head of Holofernes dating from the middle of the century.

Eighteenth century painting is represented by the Dream of St. Joseph, bequeathed, as was the martyrdom of San Lorenzo, by the Marquis of Hormazas on his death in 1827. A painting of the Calvary with Mary Magdalene and St. John by Bounocare Napoli is dated at 1748.

Amongst the other pieces, it is worth highlighting a small but interesting 16th century Renaissance tableau of the Passion made in enamel, which is currently being restored.

Silverware

The collection of silver held by the Collegiate has one or two important pieces, not just nationally but also at European level. First comes a beautiful silver-plated box covered by delicate filigree work and dated between 1274 and 1328. There is another partially silver-plated box which dates back to the 16th century whose main interest lies in the fact that it features medallions and relief-work from the medieval era. The series of boxes is rounded off by one of silver and mother-of-pearl, larger in size than the others, which originated in the second half of the 16th century. Also noteworthy is a partially silver-plated staff, which may have been donated in 1899 by the Bishop of Pamplona, Don Antonio Ruiz Cabal.

Amongst the ecclesiastical pieces it is worth noting a series of silver-plated chalices. Two are from the 16th century, some date from the start of the 17th century, while others in neo-classic style can be traced to the end of the 19th and beginning of the 19th centuries. Another piece worth highlighting in this section is a ciborium/ostensorio in silver plate whose current appearance is the result of numerous additions.

The Roncesvalles Museum also has two pairs of crowns in Imperial style, one of which, in silver, corresponds to the Virgin of the Treasure and features decorative engraving.

The silver-plated Processional Cross is another of the gifts that the Prior, Don Francisco of Navarre, made to the Collegiate, featuring in the inventory for the first time in 1578, where it was called a Guiding Cross.

Moving to another style of objects, two small sculptures should be highlighted, the most important of which is known as the Little Virgin of the Treasure. This is a wooden figure of the Virgin with the Child seated on her lap, in silver plate apart from the face and hands, which was made during the Gothic period of the second half of the 14th century. The other sculpture is in cast silver and represents St. Michael.

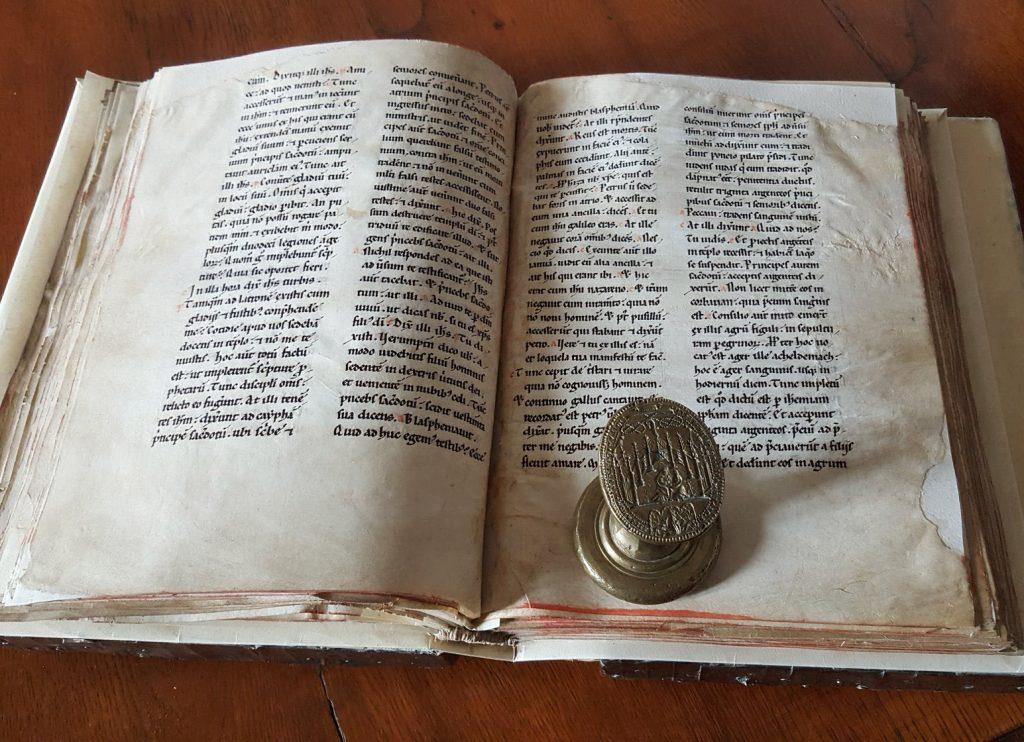

The partially silver-plated Gospels constitute one of the most outstanding pieces of Orreaga- Roncesvalles’ treasures and of medieval Navarran silverwork. It dates back to the second quarter of the 13th century and provides an example of the transition from Romanesque to Gothic. This piece evokes, once again, the parallels between the Chapter of the Cathedral and that of the Collegiate, given that both institutions boasted this rich liturgical object.

Equally notable within the so-called “treasure of Orreaga- Roncesvalles” are the reliquaries, especially the one known as “Charlemagne’s Chessboard”, thus called for its checkerboard type layout. This piece, ascribed both chronologically and stylistically to the Gothic period of the second half of the 14th century, is made up of a wooden core covered in partially silver plated sheets, translucent glazes and glass.

Another of the interesting pieces that formed part of the legacy that Don Francisco bequeathed to Navarre on his death is the Reliquary of the Thorns, in silver plate. The reliquary, in the form of an altar cross, has undergone numerous transformations over time, changes which do not, however, conceal its original Valencian-style structure.

An example of secular silverware is the silver plated cigarette case, also exhibited in the Museum. Dated at around 1760, the style of this piece demonstrates the transition from Rococo to Classicism.

Finally, another outstanding item of silverware is the famous Miramamolín Emerald, attributable, according to legend, to the one that Sancho VII “The Strong” plucked from the turban of the Moorish King at the Battle of Navas, after which it was incorporated as a symbol into the Navarre coat of arms.

The Library

The Capitulary Library is not open to the public and can only be visited on prior request for study and research purposes. Holds more than 15,000 volumes on all kinds of subjects, although the most important are on theological and philosophical topics and ecclesiastic history. There are volumes in a variety of languages: Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Basque and even Chinese. Some of the most interesting pieces, such as the 14th century manuscript, “La Pretiosa”, are exhibited in the Collegiate Museum.

Despite the fact that a good part of the documentation was transferred to official archives during the process of confiscation, there is still a considerable section of the Historical Archive left, created over the almost nine centuries that the hospital has been in existence. This documentary archive held in the collegiate offices includes scrolls, administrative books and documents relating to the internal history and external repercussions of Capitular life, etc.